Peer Review Process

Peer Review Process How great would it be to receive feedback on an application you have spent hours and hours (and dollars and dollars) crafting, compiling, and proofreading? “Impossible!” you say, “too many people apply, reviewers don’t have time for that!” Two words. Peer review.

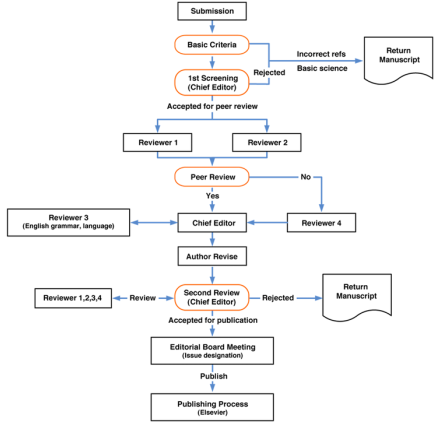

I learned about peer review from my partner, who is studying to get his PhD in psychology from Northwestern University. He recently submitted his first manuscript to a prestigious journal and told me all about the process of submitting one’s work for publication in science. This handy chart is helpful, and more information about peer review can be found here.

The critical point not illustrated in this chart is that the each reviewer writes a formal response and critique of the work they are reviewing. This is both to advise the editor about the submission, and to give the author feedback how their work can be improved in the case it is not chosen for publication.

I learned about peer review from my partner, who is studying to get his PhD in psychology from Northwestern University. He recently submitted his first manuscript to a prestigious journal and told me all about the process of submitting one’s work for publication in science. This handy chart is helpful, and more information about peer review can be found here.

The critical point not illustrated in this chart is that the each reviewer writes a formal response and critique of the work they are reviewing. This is both to advise the editor about the submission, and to give the author feedback how their work can be improved in the case it is not chosen for publication.

This is the part of peer review that amazes me most. Aside from established scientists being expected to frequently read new findings in regard to their field of study, these experts carve time out of their busy lives to review a stranger’s work. This practice is future oriented. The goal of the reviewers is not only to find the best article to publish, but to create the most fertile soil for the submissions that weren’t quite up to snuff, to grow into publishable science.

I am not alone in the art world, or even the world world, in that I am continually applying for opportunities to further my career and am usually rejected. What is more frustrating than the rejection is that I cannot think of a time I received helpful or critical feedback when my work is not accepted. Perhaps my work is overall not good enough. The point is I, and so many others, have no idea if our applications were the first or last to be rejected.

Charles Rosen said, “The death of classical music is perhaps its oldest standing tradition.” All I can think is, Why aren’t people saying the same thing about science? Why can science continue to change and grow and that not be a sign of it dying? Perhaps artists are dramatic in their word choice. I’m willing to argue that peer review, being a future oriented and altruistic practice among scientists, contributes to the advancement of science. How can artists adapt some of these practices to further our field?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed